I recently had a question from a triathlete about using Training Peaks (TP), particularly in regards to Chronic Training Load (CTL - "Fitness"), Acute Training Load (ATL - "Fatigue") and Training Stress Balance (TSB - "Form"). The questions were in regards to how you can use these metrics to plan a season or build

The first thing I will say to ensure full disclosure is that, in general, I don't use these metrics significantly in planning out a season or build. That is to say I don't plan how much TSS per week an athlete should hit and what CTL they should be at for race day. I remember a Triathlon Taren podcast about this point and that if triathlon was just about building CTL, there would be no point in racing! I do often look back at such metrics retrospectively to help me manage what is coming next, to check in on possible fatigue and to look for trends in the data (both positive and negative).

Additionally, it is essential to START WHERE YOU ARE AT and to acknowledge that EVERYTHING IS CONTEXTUAL. There is definitely not one right way to go about triathlon training and every athlete adapts to training loads and training types differently. So take what I have to say with a grain of salt and understand these are my thoughts which may not be reflective of how other coaches go about their business.

Now with that disclosure out of the way, lets take a look at 3 examples which highlight what I believe are a few key planning considerations when using TP to plan and manage your training.

EXAMPLE #1

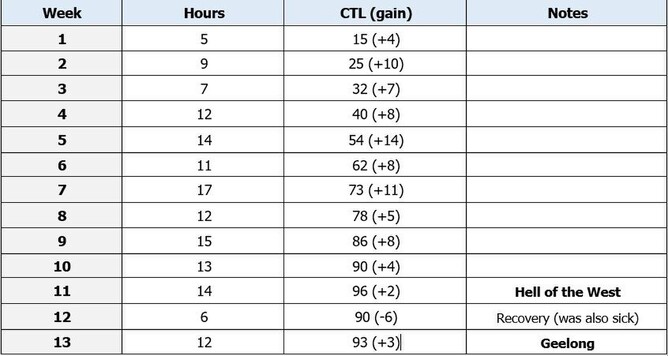

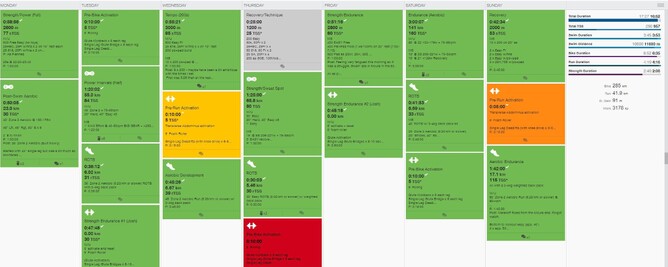

The first example is one from my own training and self-coaching. This is what I would call a "typical" build, however, this build was accelerated more so than I would normally plan for myself or any other athlete - unless you have a significant athletic history and have only come off a short break. After Cairns Ironman in June 2019, I did almost literally nothing up until November (about 5 months)! This build is over 13 weeks from November through to Geelong 70.3 in February.

Some things to take in to consideration when looking at this data;

* I have a long training history so this kind of build was manageable for me in a short time

* This build was also accelerated more than I would normally do for most athletes - I had some short term goals to reach and I had more time to recover than usual with school holidays and moving to 3 days a week work

* The increase in hours and CTL is faster than what I would plan for a 16-20 week program or a season plan

* Rather than a typical 2 or 3 week "build", 1 week rest kind of program, this was more 1 week on/1 week off. This approach was mainly because I know my body and know that I struggle to handle big training loads week after week (but at the same time I wanted the training effect the big load gives). You will also see an unusual trend in the data where the bigger training weeks don't necessarily mean a higher CTL - the bigger training weeks were much more low intensity work and the smaller weeks more high intensity...you simply can't increase both at the same time without burnout or injury!

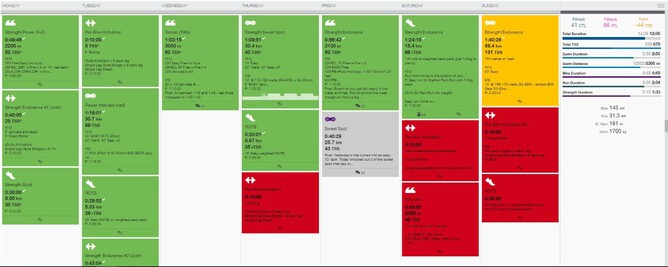

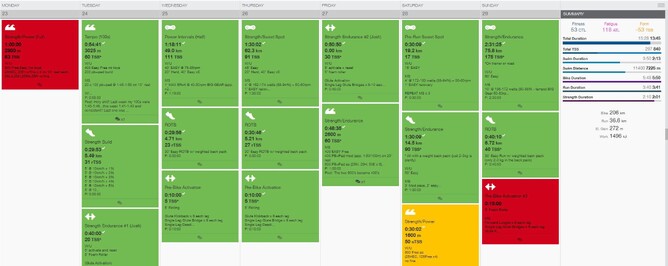

So you can see an average CTL gain of about 7-10 points per week. A safe range for an extended period of time would be more like 4-7 points per week but, again, this is all relative to the athlete, their history and their context. You can see training hours started low and, in normal circumstances, that transition to bigger weeks would be spread over a much more significant time period. But you get the idea of what a "typical" build can look like - however, over a longer time period you would find more peaks and troughs rather than the straight line in this Performance Management Chart (PMC). Below I have also included some snaps of some training weeks (4, 5 and 7) so you can get a bit of an idea of what the training looked like for this progression. Not to say this is what it should look like - just an example.

EXAMPLE #2

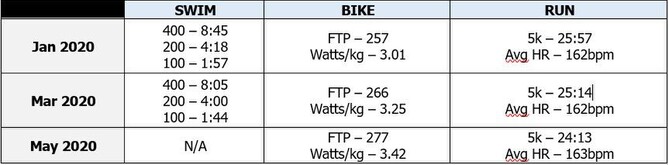

The purpose of this second example is to show that CTL is not THE way to measure improvement. It is a useful metric which can give insight when triangulated with other data (both subjective and objective), but is most certainly not the only way to measure improvements in fitness or performance.

This example is of a relatively new Smurf & Smurfette athlete who started with us in January. They came with a significant athletic history, particularly in cycling, and great motivation to get stuck in. The application of this athlete to their program has been immense, but this isn't necessarily represented in their CTL data.

From January to May of this year, the athlete has gone from a CTL of 86 to around the 100-105 range. Not a significant jump at all. The data in the table below, though, shows significant improvement in other areas.

You can see in the table that their swim, bike and run metrics have all improved. In addition to this, we have completed a couple of race specific bike/run sessions which have shown improvement in pacing and fuelling. Their CTL has stayed very level though. This program was essentially 12-15 hours per week with a more traditional 2 or 3 weeks of work followed by a recovery week.

Our focus here now is on a 70.3 in 12 weeks time, so CTL will more than likely stick around the 100-110 mark with a large focus on race specific training blocks. The improvements won't be made in CTL or "Fitness" as such, but in other areas of lesser strength to ensure the best possible performance come race day.

EXAMPLE #3

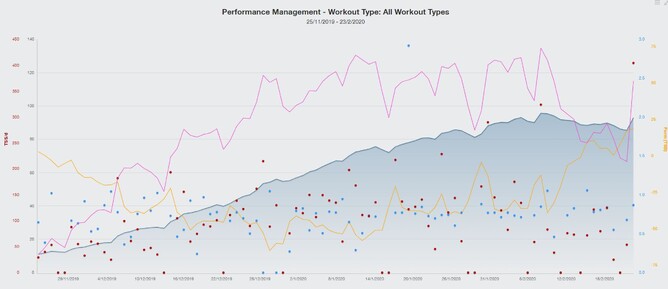

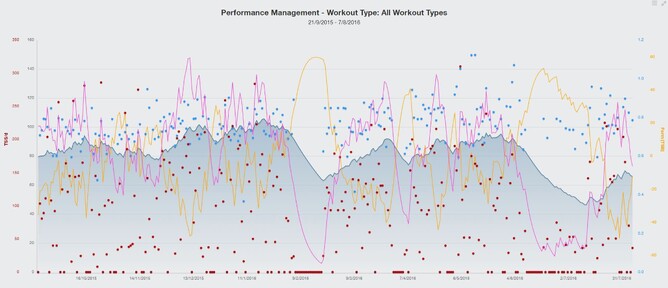

The purpose of this third and final example is to demonstrate what a "year long" season can look like. This is Smurfette's training from September 2015 through to September 2016. The basic structure of the season was;

* "Off-season" from September to November with heavy strength blocks. This included 2 to 3 sessions a week in the gym lifting heavy, discipline specific strength and 2 rest days per week to ensure we didn't overload too much. During this time, there was no speed or tempo work - it was all aerobic (other than the strength work) to ensure we managed fatigue carefully. It's important to note that strength work has an anaerobic effect so care should be taken when introducing a strength program

* Race build from December to February for Geelong 70.3

* 2 weeks recovery

* Race build from March through to June which included two 70.3 races (Putrajaya in April and Cairns in June)

* 2 weeks recovery

* Race build from Late June through to early September (World 70.3 - Sunny Coast)

Some lessons we learnt from this and some things to consider;

* Smurfette has a great ability to soak up heavy training and actually performs much better with these kind of builds. The goal was a sub 5 hour and we finally hit that at Cairns 70.3. Average training weeks were often around the 14-16 hour mark

* Despite this, we pushed for too long. Come World 70.3, Smurfette was fatigued and done. She had a good day at but wasn't able to perform at her peak

Take a look at her PMC for that year. Note, however, that she wasn't using a heart rate monitor or power meter so the accuracy of the PMC is very questionable. In particular, the time period in June and July where there looks to be no training is incorrect as she was consistently hitting 15-16 hour weeks. Despite all this, it tells a story.

The story it tells is an important but simple one. The peaks and troughs.

When you are looking at a full season, a full year or multiple years of training, it's simply recipe for disaster if you were to focus on sustaining a certain CTL or level of fitness the entire way through. What you can see in Smurfette's PMC are the peaks and troughs of blocks of significant work followed by blocks of rest. And this is contextual for different athletes. For me, I need good recovery every 7-10 days. For Smurfette, we can go hard for 3 or even 4 weeks before letting the foot off the pedal and getting decent recovery. Then you also need to consider your life circumstances and those stresses - how are you managing those around your training? Do you have a block of night shifts coming? Do you have travel for work to consider?

The key is to listen to you body and use metrics such as CTL, ATL and TSB to help inform decision making regarding training plans. Heart rate variability is another metric which is useful, but in the end, listening to your body is most important.

Improvement IS NOT linear. You will make great progress, you will struggle, you will miss sessions, you will nail sessions. But if you keep in mind that improvement comes with patience, perseverance and smart planning and training, you will do fine.

Get In Touch

So these are just a few of my thoughts - I am keen to hear yours! How do you plan your training? How do you manage a triathlon season or race build? What works for you?

Cheers,

Smurf :)